SRU history major researching Butler’s 1900s typhoid fever epidemic

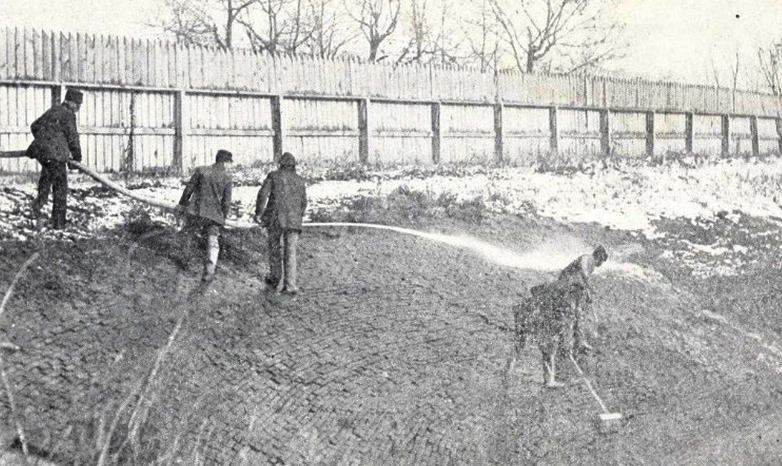

Men scrub a reservoir at Boydstown in December, 1903 following an outbreak of typhoid fever in Butler. Following the cleaning, the reservoir was refilled with filtered water and Butler’s water pipes were flushed.

June 28, 2017

SLIPPERY ROCK, Pa. - Much like the title character in Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland," Alysha Federkeil found herself becoming "curiouser and curiouser" as she ventured deeper into her tasks at the Butler County Historical Society.

FEDERKEIL

Federkeil, a Slippery Rock University senior history major from Butler, spent the summer of 2016 writing biographies of the persons buried at Butler County's North Side Cemetery and was struck by how many people died from a typhoid fever epidemic in Butler from 1903-04.

That curiosity led Federkeil to earn a job this year as a summer researcher for the BCHS, funded by a $725 grant through SRU's Summer Undergraduate Research Experience.

"I found out there really hasn't been much at all written about (the epidemic)," said Federkeil, who created a timeline project about the typhoid outbreak for her Pennsylvania History class last fall. "What really fascinates me about it is that it was such as big deal: 10 percent of the population and one in four households were affected."

More than 110 Butler residents died from the epidemic when the city's water system was contaminated in November 1903. Compared to a modern-day water crisis, like the lead contamination in Flint, Michigan in April 2014, Butler's typhoid epidemic did not gain the relative attention like other outbreaks in Philadelphia and Ithaca, New York. However, as Federkeil noted, Butler's epidemic helped drive more stringent regulations in Pennsylvania, with the establishment of the state's Department of Health and Water Supply Commission in 1905.

According to the Mayo Clinic, typhoid fever spreads through contaminated food and water or through close contact with someone who's infected. Signs and symptoms usually include high fever, headache, abdominal pain and either constipation or diarrhea.

Today, most people with typhoid fever feel better within a few days of starting antibiotic treatment, although a small number of them may die of complications. Vaccines against typhoid fever are available, but they're only partially effective. Vaccines usually are reserved for those who may be exposed to the disease or are traveling to areas where typhoid fever is common.

"It was a chronic problem and it's important to illustrate that because the epidemic didn't come out of nowhere," Federkeil said, "which is what the newspapers would have you believe once it hit in 1903."

Butler residents were exposed to contaminants when the city's water company switched off its filtration system for a few days while a new reservoir was being constructed. The epidemic lasted three months, during which there were boil advisories and the city's water pipe systems were flushed.

"It was a major outbreak," said William Bergman, assistant professor of history who is mentoring Federkeil through her research. "The problem we're looking at is not to just recount what happened but to think about the ways in which the environment in the rural areas around the city contributed to the disease inside the city."

Typhoid was more common in rural areas at the time, but increased contamination in the Connoquenessing Creek that surrounded Butler contributed to the epidemic. In addition to human and livestock waste from the rural areas, industries such as oil drilling and coal mining further polluted the creek that fed into Butler's water supply.

Federkeil's research this summer will also involve plotting out the typhoid cases on a map of the city based on newspaper and board of health records and information gathered at the BCHS, the Butler County Courthouse and the genealogy room at the Butler Area Public Library.

"Generally it's the poor people who get hit harder and in Butler that wasn't the case," Federkeil said. "It was pretty even throughout. I think that's interesting about this epidemic in comparison (to others)."

The plan, according to Bergman, is to have Federkeil present her research as an article in a peer-reviewed journal, such as Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, or present a poster at a conference, such as the Pennsylvania Historical Association's annual meeting in October.

"This project will provide her a much better experience in terms of elevating the sophistication of her research and, hopefully in the end, her writing," Bergman said. "She's skilled at both but this will make her even stronger."

"I never imagined that I would be working on something like this while I was at SRU," Federkeil said. "This opportunity has helped me get more invested. I've been able to see the broader consequences of the epidemic. I wouldn't have necessarily thought to do that before."

MEDIA CONTACT: Justin Zackal | 724.738.4854 | justin.zackal@sru.edu